When you actively try to strip away what few small threads of joy there are in an otherwise passably interesting calendar event, I'm sorry, you're just mean.

Why do we leap day? We remind you (so you can forget for another 4 years)

Interestingly, that headline was sanitized from when I first saw the story on Apple News, leaning much more heavily into the perpetually aggrieved feminist angle.

The reason leap days exist — and their surprising gender-bending traditions

In fact, that picture above in the link is more in tune with that original headline (more on that in a moment). Here's the picture they are currently using for the article:

The "gender-bending" element wasn't even a focus of the story, in fact it was a pretty small part of what is basically a serviceable example of the typical quadrennial puff piece on leap years, explaining that "it actually takes Earth 365.242190 days to orbit the sun" as if we're all third graders, our eyes widening with wonder, and that people born on February 29 can finally get to have a birthday (yuck yuck).

But, a bit more than halfway through it begins to explain that most leap day lore "worldwide revolves around romance and marriage, including an old tradition."

According to one legend, complaints from St. Bridget prompted St. Patrick to designate Feb. 29 as the one day when women can propose to men. The custom spread to Scotland and England, where the British said that any man who rejects a woman's proposal owes her several pairs of fine gloves.

Okay, so a calendar version of a Sadie Hawkins dance.

That sounds harmless enough, but then NPR Associate Editor Rachel Treisman ("she/her, in case you were completely flummoxed over her gender) decided to turn to Katherine Parkin, a professor of American Social History at Monmouth University:

The real origin … is that people have historically liked to challenge gender and gender roles.

Sure. I guess, after, historically speaking, they were able to solve the whole not starving or getting eaten by a lion thing.

'And in the case of marriage, to have a reversal of that power, I think is really unusual,' she added. 'And it ties perfectly with this unusual date. Where did it come from and where did it go? And so I think it really plays well into people's imagination and playfulness.'

You know why this is starting to sound like a set up?

Because it's a set up.

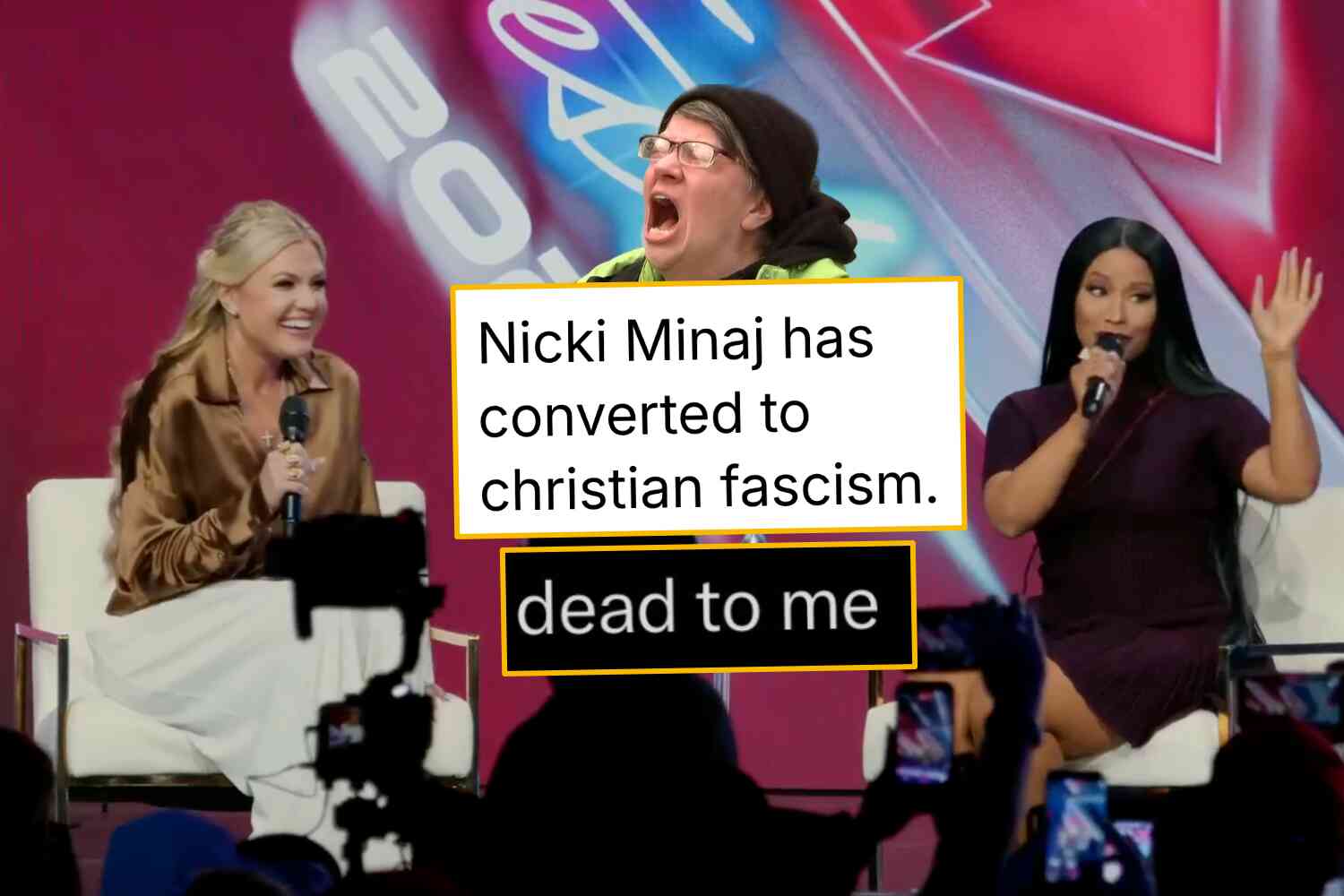

But Parkin says her research points to darker undertones behind the tradition — namely, that it was actually intended to ridicule women.

'It's proving to ... reinforce that it's a leap year and that this tradition exists and yet at the same time telling women, you really don't want to do this because it looks bad for you,' Parkin said. 'As a historian, I look back to this tradition and see it as part of an American desire to offer women false empowerment.'

Of course you do, professor. As a historian.

Whenever someone feels the need to inject their credentials into an argument they are making, they don't have an argument good enough to stand on its own.

Speaking of which, what is her evidence of this intent to ridicule women and offer them false empowerment?

Hundred-plus-year-old postcards.

She points to the proliferation of postcards in the 20th century — which people would send each other across all kinds of relationships — that portrayed women who proposed to men as desperate, unattractive and aggressive, such as holding butterfly nets and pointing guns at guys.

Her entire thesis, as a historian, is based on postcards.

I'm sorry, a "proliferation" of postcards.

She literally has a page on her website dedicated to this body of, ahem, research, called the "Leap Year Postcard Database."

That link takes you to a handful of cherry-picked cards. Here's one:

The woman is definitely being portrayed as unattractive but the man isn't exactly a catch, either. In any case, these are meant to be absurdist humorous caricatures.

The problem with Parkin's thesis, which she formulated as a historian, is based on there being a "proliferation" of such postcards. I mean, basing it on postcards is absurd enough, even a proliferation of such, but unfortunately for Professor Parkin the historian, it doesn't stand up to even passing scrutiny.

And when I say scrutiny, I mean looking at her own database.

I scrolled through them all, the vast majority of which come from 1908 (she must had stumbled across an estate sale or something). The handful she chose to highlight are just about it. The collection is otherwise largely unobjectionable early-20th-century fare.

First, women are rarely portrayed as unattractive and aggressive, quite the opposite in fact.

The man here is being portrayed in the typical commitment-fearing comical sense.

And on the subject of men, does Parkin consider this a positive portrayal? It's literally labeled, "Leap Year Drunk."

Or how about this? Are we supposed to think less of that woman and more of the man? Really?

Most of the rest come across more as standard Valentine's Day cards than anything else.

Again, none of those women are unattractive.

You have to wonder what compels people to manufacture nonsense like this when they don't have to. Back in 1908, women couldn't vote. Harp about that if you want to wallow in historical misery, but you can do that without having to make things up about postcards and leap year.

This is the state of our intellectual elite.

No matter. Enjoy your extra day, and if you are a man...

P.S. Now check out our latest video 👇