I grew up in a safe suburb like many middle-class American kids in the ‘90s.

I had a paper route and a dog, and I rode my bike to my friend's house down the street - all that classic Norman Rockwell stuff we enjoyed as our country rode the wave of the Reagan boom. Naturally, I took it for granted. I just assumed that was what life was like for almost everyone.

That all changed when I visited a 3rd-world country for the first time as a 19-year-old Marine Corps infantryman.

Going from middle-class Ohio suburbs to Fallujah, Iraq is quite the culture shock. I'll never forget the first night. After a C-130 flight into Al-Asad, we were loaded onto a 7-ton truck for our midnight arrival. As we traveled down the main strip to our Forward Operating Base outside the city, I took in the alien architecture - the mosques, the mansions, the humble homes and apartments. They all had one thing in common. Around every property and home were massive walls topped with glass, spikes, or razor wire. Doors were closed behind metal gates. Windows were covered with bars. I had left America, formed by 2,000 years of Christian moral norms and high community trust, and entered a place outside the West - a place with very different norms.

Over the year I spent there, I watched kids walk to school past craters as gunshots went off in the background, acting as if it was all completely normal. For them, it was. I saw trash dumped wherever it was convenient to dump it. I drove by bullet-riddled cars that contained bullet-riddled bodies, whether from a road rage incident, gang activity, or something else (who knew?). No one seemed to care, and people carried on like it was nothing out of the ordinary. I watched as a soccer field we had just built for the local children was raided for dirt (yes, high-quality dirt is a hot commodity in Fallujah). And everywhere I went, I saw the same thing: Razor wire and walls.

Fallujah might seem like an extreme example, but it's not the only place I saw things like this. A few years after Fallujah, I was in Peru for a joint training exercise with their special forces. During my time off in Lima, I saw a familiar sight: Razor wire, walls, gates, and bars. It turns out that this stuff is everywhere around the world.

An orphanage my church supports in Haiti features walls and wire to protect the kids inside from the murderous gangs and traffickers currently running free in that country. Even in certain parts of the US, such as the south side of my city in the blocks around a homeless mission where I volunteered, you see walls and barbed wire protecting property and bulletproof glass barriers protecting gas station attendants.

Razor wire might seem crude and barbaric to sheltered NPR listeners in Boulder or Ann Arbor, but outside the West, razor wire is the norm. In places where there is little rule of law or Christian influence, it's ubiquitous.

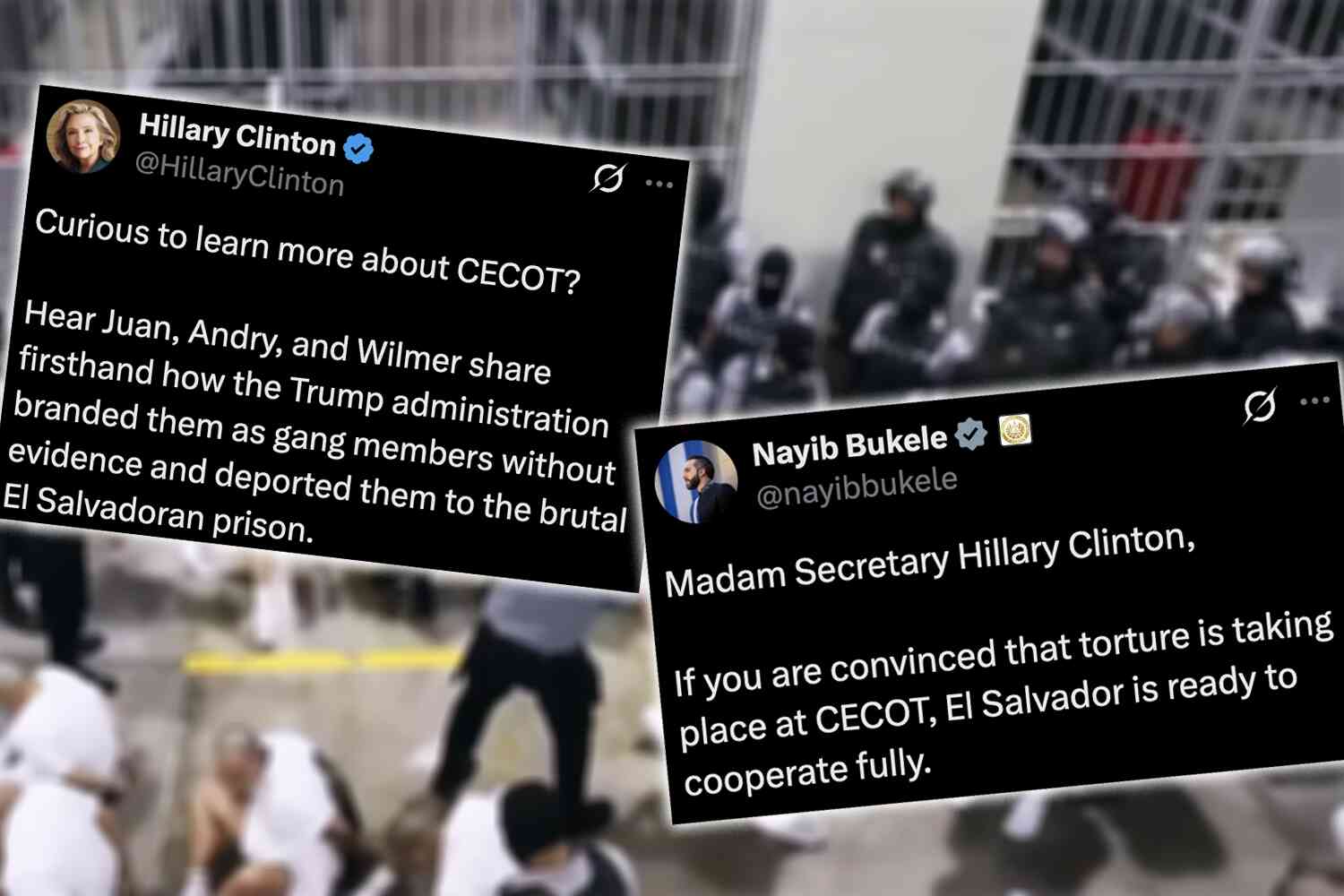

American states are now in a figurative (hopefully it stays that way) civil war over whether our southern border should be using barriers and razor wire to protect our country. This comes after the Biden administration has allowed between 8 to 12 million third-worlders into this country with no vetting or plans to assimilate them. Ecuadorians, Somalians, Iranians, and Iraqis are all pouring across the border, and they're bringing their cultural values with them. They are no stranger to lawlessness and razor wire.

It's easy to be nostalgic for an idyllic ‘90s America, but even in 2024, we have so much that we take for granted. Walk through any middle-class neighborhood in America and the security walls and razor wire are still absent. We still enjoy a level of trust and rule of law that is unheard of in the rest of the world. But for most of us, we'll never appreciate what we had until it's gone.

That's the choice we face today in America. We can either secure our border with walls, razor wire, and whatever else it takes, or we'll soon be forced to build those walls and razor wire around our homes.

We live in a sin-cursed world where corrupt leaders ignore laws and the strong prey on the weak.

The razor wire is inevitable. It's just a matter of how close to your home you want it.

P.S. Now check out our latest video 👇

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Not the Bee or any of its affiliates.