In recent days, Somali immigration has dominated headlines, sparking heated debates about everything from national security to economic impact to cultural identity. The conversation has grown loud, emotional, but has rarely moved beneath the surface.

Here's one side:

And the other:

It's worth considering the deeper and more foundational issues at play here.

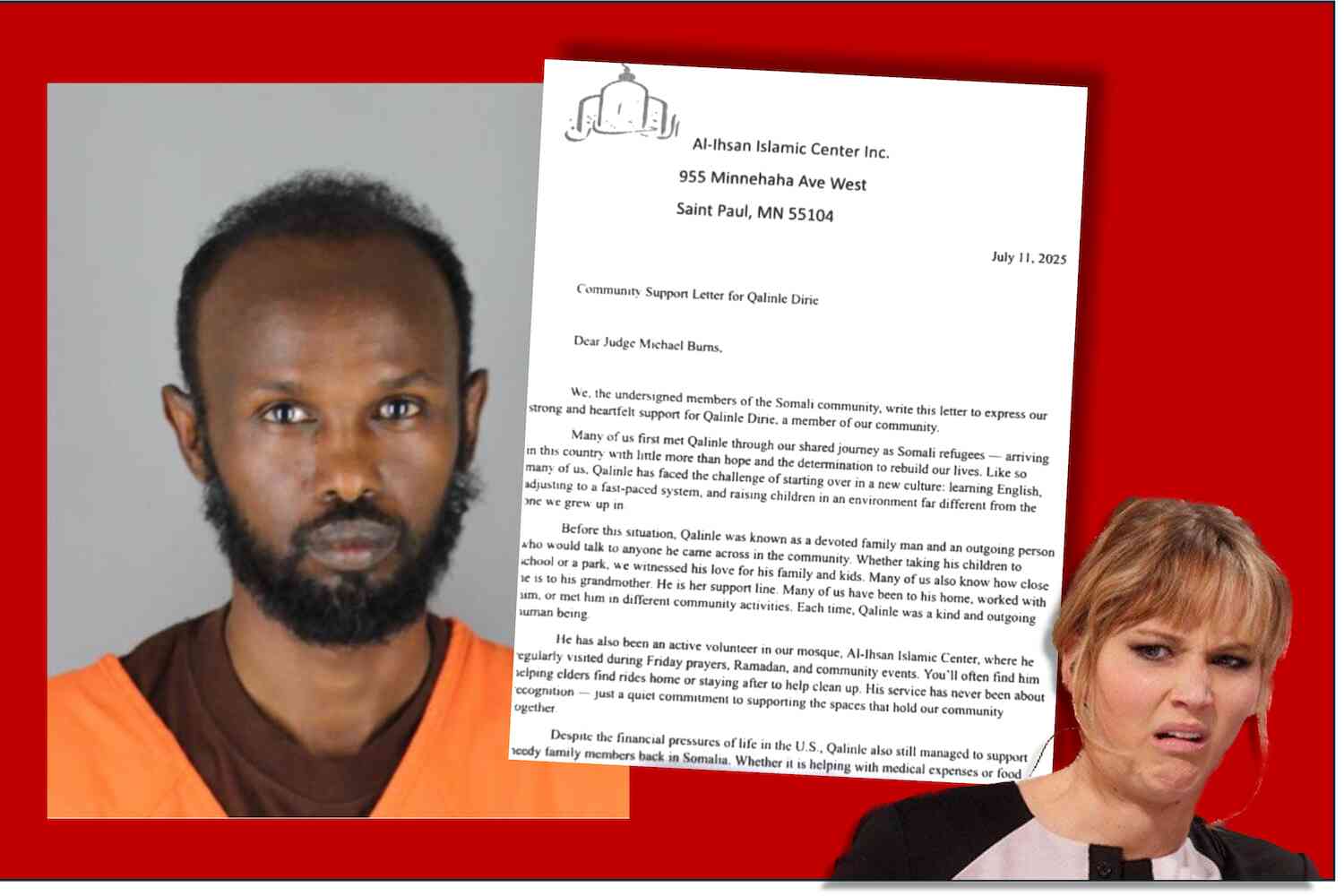

To do so, let's go back to late May, when a Minnesota jury convicted Qalinle Ibrahim Dirie, a Somali immigrant living in Minneapolis, of abducting and raping a twelve-year-old girl. The case was horrifying, and the evidence was so overwhelming that the jury took little time to reach a verdict. But the most revealing part of the tragic story came after the conviction, when the Al-Ihsan Islamic Center in St. Paul submitted a "community support letter" on Dirie's behalf.

The jaw-dropping letter asked the judge for leniency. As Not the Bee reported at the time, it described Dirie as a "deeply good man," praised his commitment to the mosque, highlighted his service to elders, and emphasized his financial support for extended family in Somalia. The portrait they painted was not of a predator, but of a misunderstood pillar of the community whose crime was framed as a tragic lapse in judgment rather than a violent assault on a child.

Buried in that letter was one line that explained the entire logic of their defense: Dirie, they wrote, had long struggled with "the challenge of starting over in a new culture."

We simply must consider what that phrase - "a new culture" - reveals. Dirie was not formed by the moral expectations that most Americans still assume to be shared. He was shaped by the norms of a different moral imagination, a different conception of guilt and honor, a different understanding of what makes a man "good."

And when those two worlds collided in a Minneapolis backyard, the instinct of the Islamic center was not to uphold the moral standards of the society whose laws had just been violated. Their instinct was to uphold their man, according to their communal loyalties.

The letter is more than a defense of a criminal, which is why I'm bringing it up here. It is a window into the deeper reality that we have come to reject the "melting pot" conception.

America is no longer (and hasn't been for some time), a civilization made of different "flavors" from around the globe.

America now contains competing civilizations, each with its own ethical foundations, each discipling its people toward different standards of what is honorable, what is shameful, what is forgivable, and what is beyond the pale.

When a religious institution can describe a convicted child-rapist as a "deeply good man," the problem is not simply misjudgment, it is worldview. Different moral worlds are operating simultaneously, and they do not agree on the most basic definitions of right and wrong.

This is not about race. It's not xenophobia, nativism, or even about immigration status.

This is about moral architecture.

Christianity shaped the conscience of the West - its legal assumptions, its view of children, its belief in the equal dignity of every soul, its insistence that the strong protect the weak, its moral revulsion at sexual exploitation. These convictions are not arbitrary. They come from Scripture's vision of humanity made in the image of God, individually accountable before a holy Judge.

But Dirie was not formed by that vision. He was shaped by the cultural and religious expectations of Somali Islam, where communal honor frequently outweighs individual guilt, where the integrity of the group is often prioritized over the suffering of the victim, and where personal righteousness is measured more by obligations to one's clan than by adherence to universal moral law. When the mosque praised him for volunteering and sending money home, they were evaluating him according to their system of righteousness, not ours.

And that system does not produce the same instincts when a vulnerable child is harmed.

So we are left with a very uncomfortable truth:

We are no longer a nation bound together by a shared moral framework.

We may share geography, but we do not all share the same conception of what goodness is, what justice demands, or whose pain deserves empathy.

A society can benefit from ethnic diversity. It can absorb linguistic diversity. What it cannot survive, however, is moral divergence at the level of first principles.

The real issue is not whether Dirie could, or Somali immigrants can, adapt to a "new culture." The question is whether America still has one.

P.S. Now check out our latest video 👇

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Not the Bee or any of its affiliates.