If it was confined to the intellectual sewer of Twitter, I'd leave it alone, but the ever-increasing prevalence of woke revisionists and anti-Western activists attempting to influence the content and character of American history curriculum around the country forces my hand.

You may have seen this little meme floating around cyberspace:

I've been teaching American history in a public school for 19 years now. In that time, I've seen plenty of alterations, changes, and adjustments being proposed and promoted for our course content from a variety of sources. So, if I may, allow me to offer a few observations about this "schools are failing to teach about Native Americans" complaint.

1. Textbooks and courses can't cover everything, particularly for junior high and high school levels. The average person has probably never considered the immense challenge to give adequate time to "significant events" of America's history. Particularly given the fact that everyone has their own opinion of what constitutes significant.

For instance, I love the American Revolutionary era and find it to be the most important and critical to teach. But it only took a year of spending two weeks on the founding, then failing to advance past Vietnam by the time the school year ended, to realize my timeline needed revision. I've had to whittle it down to four days for the revolutionary era, and even that strains the pacing schedule.

Everyone can pick their pet issue and demand it be taught. For me, I think Washington's Farewell Address should be analyzed in every textbook, his brilliant spy network detailed and diagrammed, and the wilderness campaigns of revolutionary guerilla fighters (which included the pivotal killing of Simon Frazier) revealed as being perhaps most responsible for our independence. But if I indulge that preference, many topics that others consider a necessity will be shafted.

From my experience, U.S. History should be a two-year course. Year one, cover pre-American independence through 1900, and then have a full year to cover the entire 20th and 21st centuries. Limiting the subject to one year is fine if you are just looking to introduce general knowledge. But if that's what we're agreeing to, don't complain about specifics not being taught.

2. Adults care more about history and therefore pay more attention to these discussions. With as motivated as young people may be about cultural crusades on social media, that doesn't translate to an equal motivation to study and learn history. I've had more than a handful of adults approach me after hearing me speak and say, "Man, I wish I had a history teacher like you when I was in school." They mean it as a compliment and I thank them, but the truth is they probably had a better one than me. They just didn't care then like they do now.

Which means, there's a very high degree of likelihood that many of these memes disgruntled adults are pushing now about what is missing from textbooks were probably in their own textbooks that they just didn't read.

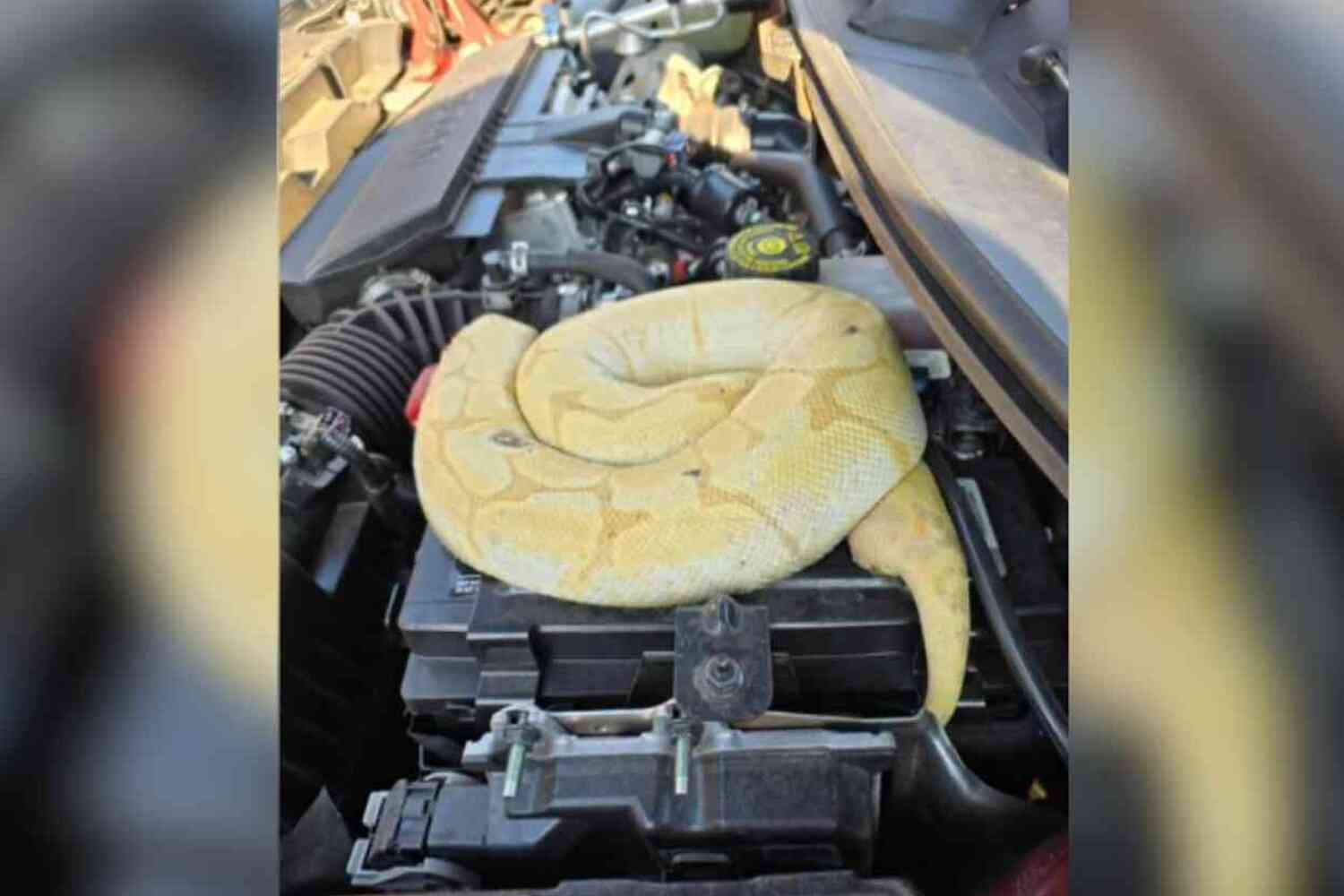

Anecdotally, during the race riots of last summer I had a former student post publicly that they were never taught George Washington owned slaves. This is a page from the history book I've been assigning kids to read cover to cover for over a decade:

The problem wasn't that she wasn't taught, it was that she hadn't cared enough (at the time) to read what was assigned.

3. The rules always change. To be frank, entire powerpoints and lectures need to be rewritten these days because references to "Indians" are now termed offensive. It's honestly much easier for a lot of teachers to just say, "forget the lecture, read this woke-approved handout and let's move on" than willfully wade into a terminology minefield. In this way, the woke are the biggest enemy of their own objectives:

4. This stuff in question is in textbooks today. Here's a page from the 8th grade textbook used in my school. It is published by textbook giant Pearson.

I truly don't mind input from passionate people about what they think belongs in American history curriculum and what doesn't. I would count myself among the number of people that think academia has lost its way when it comes to what are the most important aspects to highlight. But I think petitions and remonstrances about the issue would carry more weight if their accuracy to hyperbole ratio was just a bit more balanced.

P.S. Now check out our latest video 👇

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Not the Bee or any of its affiliates.